Reception and Circulation

In 2019, it will be one century since the Dutch historian Johan Huizinga published his international bestseller Herfsttij der Middeleeuwen. Huizinga’s much-discussed historical essay described the “forms of life and thought” in the late Middle Ages (i.e. the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries) in France and the Burgundian Low Countries. In 1986, the leading medieval scholar Frits van Oostrom described the book as “the most influential study (…) that was ever written by a Dutch ‘alpha’.”[i] (1986: 202) Its influence reaches far beyond its national and linguistic borders.

Historiography or Literature?

In terms of the content of the work, Huizinga aimed to offer a new perspective on the courtly culture of the late Middle Ages: he did not consider its riches and pageantry as evidence of the flourishing and wealth of its culture, but rather as purely external displays that masked the vacuity and decline of courtly culture. Huizinga’s book was not primarily based on archival research, but on the visual arts and on literary sources and chronicles. This was highly exceptional in the historiography of his day, which championed a strict approach to source materials. Huizinga interpreted his sources and brought them together narratively in an almost literary essay.

The work was therefore not appreciated by Dutch historians of the period; it was deemed unscientific and even old-fashioned, while in hindsight it was in fact very innovative and even ground-breaking. Van der Lem writes that the “appearance of Huizinga’s Herfsttij (…) (was) an unusual event in Dutch historiography. The subjects and the way they are treated were completely new in comparison with the uniform tradition.” According to him, the academic historians lacked the talent to judge the book on its merits (1993: 149).

A well-known story in the rejection of Herfsttij in the Netherlands is the statement of the archivist Samuel Muller in 1920, who judged Huizinga’s book to be a failure (Quoted in Van der Lem 1993: 149). He questioned “whether Professor Huizinga has written history or literature, because literary praise is not appropriate for a historian.”[ii] Matters were not helped by the fact that Dutch literary critics such as P.N. Van Eyck and Menno ter Braak did praise the work. While appreciation for the book as ‘literature’ was perceived negatively by historians, it is precisely this praise that enabled Herfsttij to become world literature. As indicated above, according to Damrosch, one of the conditions of this process is that a book is read as ‘literature’.

Despite its mixed reception, three editions of the book were printed in relatively quick succession (1919, 1921, 1928). The second edition was also a revised edition. Under pressure from his publisher and readers, it was only in the third edition that Huizinga agreed to include illustrations and to translate the many quotations from late medieval French poetry, which he apparently assumed readers would simply understand.

Historiographers now generally consider the work to be ground-breaking. In 1990, Bouwsma attempted to describe why the book was so historiographically innovative: “his rebellion against the tendencies dominant in the historical establishment of his time was fundamental; he rejected its scientific pretensions, its belief (…) in progress, and its naive confidence that the facts speak for themselves.” (326) The historian himself was central to Huizinga’s approach: he bore a responsibility with respect both to the past and the present through the questions that he posed to his sources and data, and these questions depended on the personal insights and personal imagination of the historian.[iii]

[i]“de meest invloedrijke studie (…) die ooit door een Nederlandse ‘alfa’ werd geschreven”

[ii] “of professor Huizinga nu geschiedenis had geschreven of literatuur, want literaire lauweren waren voor een historicus niet weggelegd”

[iii] Nevertheless, Huizinga’s view of historiography was not unique internationally. However innovative and unconventional Huizinga’s essay was, it was aligned with the new sounds that Tollebeek claims were emerging abroad: “Huizinga’s cultural-historical method was closely aligned with the historiographic innovations that were being propagated by the Warburg Institute in London and the Annales in France, among others.” (1990: 200)

Source:

Brems, Elke and Réthelyi, Orsolya. 'Rescuing something fine. Huizinga's Herfsttij der Middeleeuwen as World Literature.' In: Theo D'haen (red). Dutch and Flemish Literature as World Literature. London/New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2019

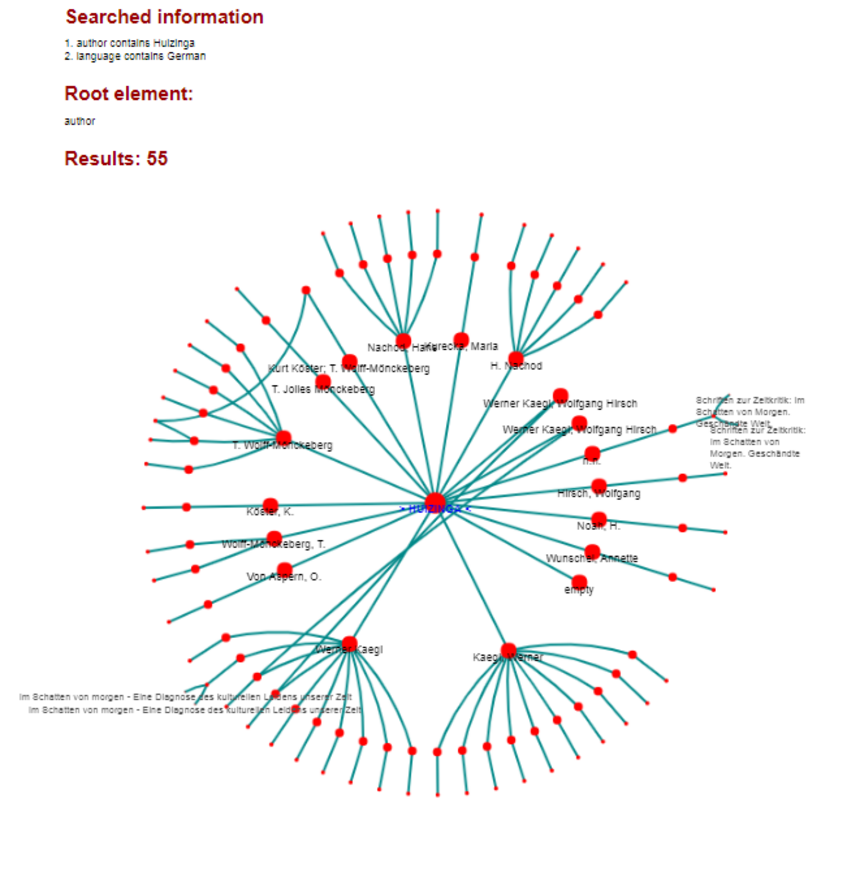

Huizinga in German translation