Herfsttij der Middeleeuwen: the German Translation

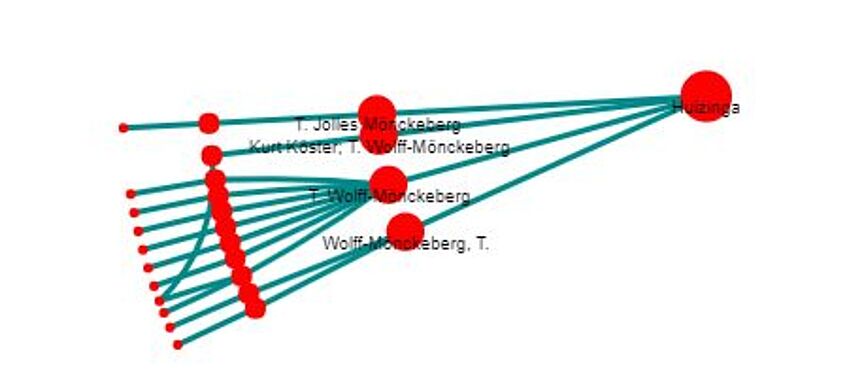

Herfsttij der Middeleeuwen was and continues to be most popular in the German-speaking world. It was first published there in 1924 by Drei Masken Verlag, in a translation by Tilly Jolles-Mönckeberg, the former wife of one of Huizinga’s best friends, André Jolles. Hugenholtz states that “the book was reprinted much more often in Germany or Switzerland than in any other country outside the Netherlands.” (1973: 91) Interest in Switzerland may be explained by the fact that Herfsttij is in a certain sense a response to the monumental work Die Kultur der Renaissance in Italien (1860) by the Swiss scholar Jacob Burckhardt. The German translation went through five editions during the interbellum alone (including the first 1924 print). Senger claims that the global success of Herfsttij is due to the German translation (2004: 6).[i] The translation was immediately celebrated in Germany, for example by Hermann Hesse, who wrote that books like Herfsttij are rare “as it is a rare stroke of luck, when a great scholar is at the same time a great writer.”[ii]

(Quoted in Senger 2004: 7) According to Krumm, who researched the German reception, there was a widespread consensus that Herfsttij was a masterpiece: “Huizinga became a 'highly respected' historian in Germany.”[iii] (2011: 241-2) He nevertheless notes that the work quickly became a monument, and people thus rarely engaged with it actively: “Thus Herbst des Mittelalters, after only a few years, had become a monument of historical research, as inevitable as immovable.”[iv]

Source:

Brems, Elke and Réthelyi, Orsolya. 'Rescuing something fine. Huizinga's Herfsttij der Middeleeuwen as World Literature.' In: Theo D'haen (red). Dutch and Flemish Literature as World Literature. London/New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2019

[i] “Er verdankt sich zum guten Teil der deutschen Uebersetzung.”

[ii] “wie es überhaupt ein seltener Glückfall ist, wenn ein grosser Gelehrter zugleich ein grosser Schriftsteller ist.”

[iii] “Huizinga wurde in Deutschland zu einem ‘rasch hoch geschätzten’ Historiker.”

[iv] “So schien Herbst des Mittelalters schon nach wenigen Jahren zu einem Monument der Geschichtsforschung geworden zu sein, ebenso unumgänglich wie unbeweglich.”

The impact of the German Translation

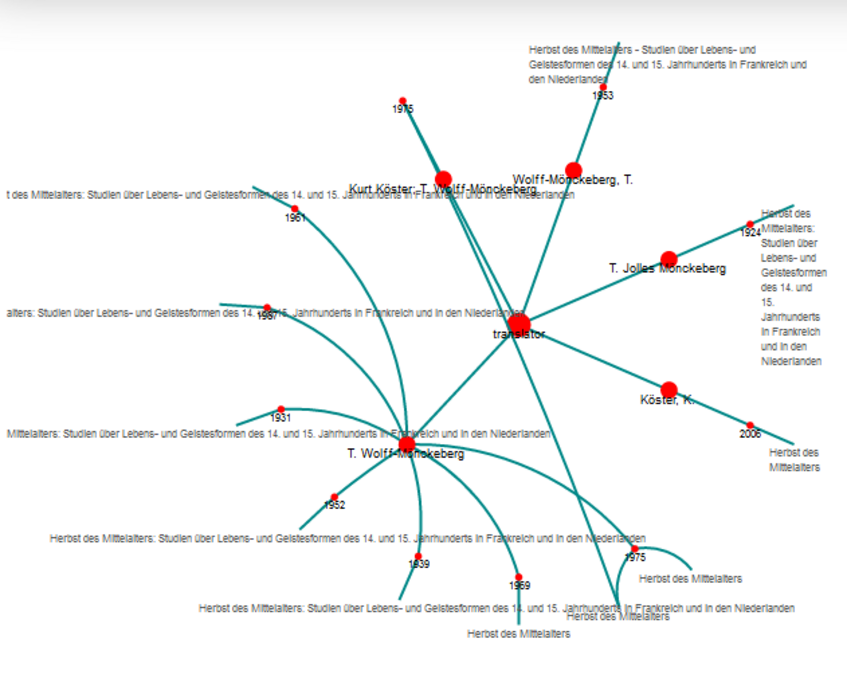

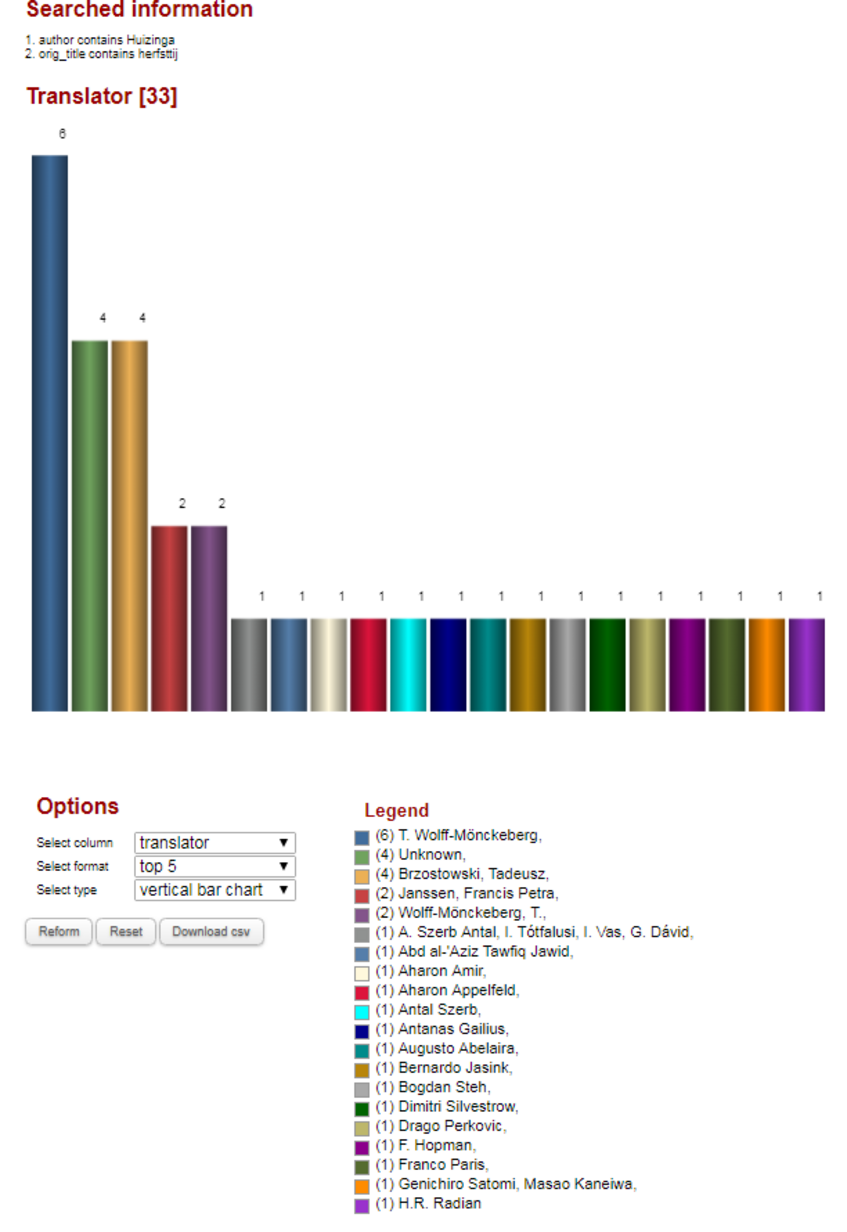

Two important changes in the 1924 German translation influenced the subsequent publication history of the work (including in other languages). The author and publisher agreed that there would be 22 chapters instead of the original 14 and they decided to include illustrations. Huizinga himself contributed to the translation significantly and he thus clearly supported these changes. He agreed with the critique that the length of the chapters varied excessively and that the chapter titles were unclear. He was also very conscious of translation problems, even between Germanic languages as similar as German and Dutch. He appears to have been a proponent of a so-called foreignizing translation. In his introduction to the German edition, he wrote: “Why should we be so eager to obliterate fearfully the traces of what is foreign in that which is of foreign origin?” (quoted in Köster 1953: XIV)[i]

In 1953, Kurt Köster revised Jolles-Mönckeberg’s translation to update it. In his foreword, he describes the ‘untouchable’ status of the work: “A work that had great impact can not really be judged any more.”[ii] Nevertheless, the fact that he updated an existing translation is an evaluation in itself: it signifies that the book still needed to be ‘actualized’ in Germany, to be accessible to new generations.[iii]

Source:

Brems, Elke and Réthelyi, Orsolya. 'Rescuing something fine. Huizinga's Herfsttij der Middeleeuwen as World Literature.' In: Theo D'haen (red). Dutch and Flemish Literature as World Literature. London/New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2019

[i] “Weshalb sollte man bei dem, was fremden Ursprungs ist, die Spuren des Fremden allzu ängstlich verwischen?”

[ii] “Ein Werk, das grosse Wirkungen gehabt, kann eigentlich gar nicht mehr beurteilt werden”

[iii] Köster writes in his foreword: “Es erwies sich als notwendig, mit dieser Arbeit der textlichen Angleichung eine durchgreifende sprachliche Ueberarbeitung der älteren übertragung zu verbinden.” XII