Huizinga in Hungary

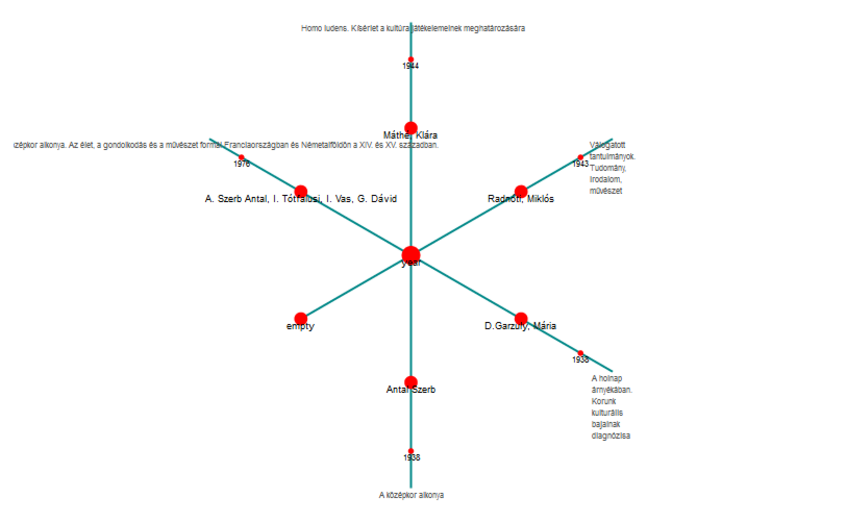

Herfsttij was first published in Hungarian in 1938 under the title A középkor alkonya [literally The Eve/Decline of the Middle Ages] by the Athenaeum publishing house in Budapest, in the series The History of European Culture [Az európai kultúra története], without illustrations, notes, a prologue or epilogue.[i] As stated on the cover, the book was translated by Antal Szerb and a note on the inner cover of the edition specifies that the translation was made from the 1937 English edition printed in London (Huizinga 1938: i).

Despite these specifications, neither the source language, nor the identity of the translator is a straightforward case. According to the contract drawn up between Huizinga and the publishing house on 12 November 1937, both parties agreed that the Hungarian translation would be made on the basis of the English version and all further abbreviations should only be made with the permission of the author (Balogh 2009: 53). Balogh argues that it was probably the Hungarian publisher’s decision to use the considerably abbreviated English version without an introduction or notes (even though this was already outdated at the time if compared to the third and latest German edition of 1931), because of the limitations of the series in which it was to be published, and the presumption that the shorter version would be more attractive to Hungarian readers. The contract should thus be interpreted as Huizinga’s demand that at least no further abbreviations should be made (Balogh 2017: 51-53). The contract also specifies the name of the translator, Rudolf Szántó, a translator whose known translations are from German and French. It is not clear why the publishing house finally commissioned Antal Szerb, the renowned literary historian and novelist for the translation.[ii]

The picture is further complicated by the fact that the first chapter and a half of this edition, and parts of several further chapters were evidently translated from the German edition of 1931 (or later). Based on a detailed textual comparison, Balogh reaches several important conclusions: (i) There were (at least) two translators at work, initially using the German edition and later mainly relying on the English version as source text. (ii) While the first chapter, translated from the German, is a vivid rendering of Huizinga’s elaborate literary style, the majority of the text, translated from the English version, is bland, often careless and inconsistent. (iii) The title, translated from the English, can most probably be attributed to Szerb. The identity of the translator is a key factor in the Hungarian reception of the work (Balogh 2017: 54-64). The figure of Antal Szerb, who continues even now to be an iconic figure in Hungarian literary history has in a way become merged with the Hungarian Herfsttij and plays an important role in the lasting popularity of the work in Hungary.

[i] Other volumes in this popular series were, for instance, Frantz Funck-Brentano L'Ancien régime, Christopher Dawson The Making of Europe: An Introduction to the History of European Unity, etc.

[ii] ”Antal Szerb (1901-45) is chiefly remembered for his widely-read History of Hungarian Literature (Kolozsvár, 1934). […] His last major work was A History of World Literature (1941), in which his enthusiasm for the values of European civilization found an outlet in an age when this civilization appeared to be disintegrating. Szerb died of starvation and privation in a forced labour camp in Western Hungary.” (Czigány 1984).

Huizinga in Poland

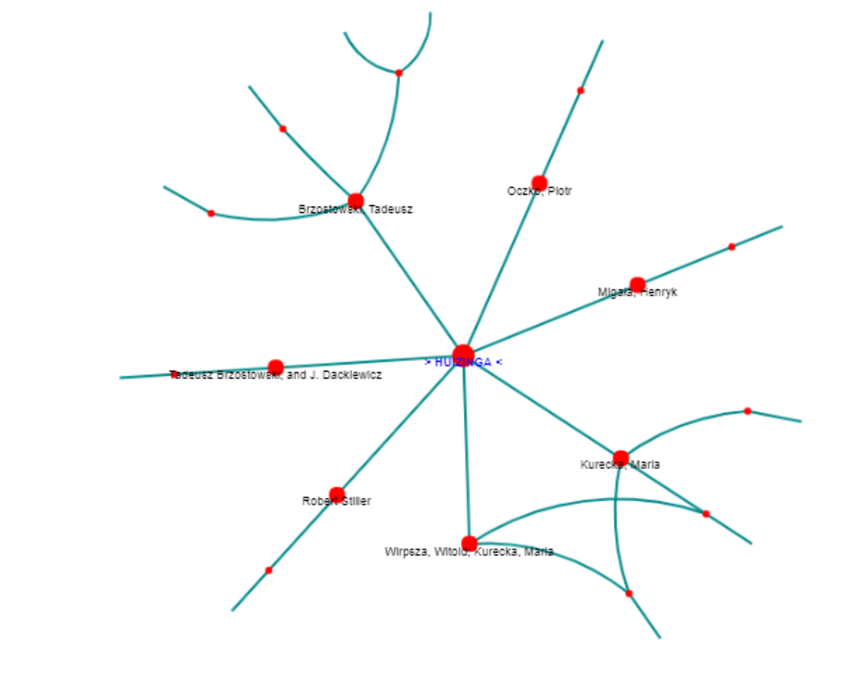

The first Polish translation of Herfsttij was published in 1961 under the title Jesień średniowiecza [literal translation: The Autumn of the Middle Ages].[i] The translation was made from the 1953 German edition by Tadeusz Brzostowski, a historian, philologist, and translator of Latin and German, while the poetry fragments were translated by Jadwiga Dackiewicz. The edition was published with several paratexts. These include a lengthy foreword by Henryk Barycz, the archivist and professor of early-modern history at Krakow University, who explores the cultural connections between Poland and the Low Countries as well as providing a biography of Huizinga. The volume also includes a historical essay on Herfsttij and cultural history by Stanisław Herbst, a modern historian and professor at the University of Warsaw, as an afterword.[ii] The book includes a selection of 24 picture plates in black and white and colour and it was reprinted at least eight times.[iii]

Relations between the Polish translations of Huizinga, data from the DLBT.

Jesień średniowiecza was Huizinga’s first complete book to be published in Polish. Translations of Huizinga’s Erasmus and Homo Ludens were soon to follow.[iv] However, Huizinga had been known to the Polish public before the publication of Herfsttij, since the first discussion of the work of “the famous Dutch humanist” appeared in the period 1946-1948 (Biesiada 2014). In an article devoted to the reception of Huizinga in Poland, Wojciech Lipoński describes how the 1961 publication of the Polish translation marks the end of the Stalinist period in Poland, during which books by humanist thinkers from Western Europe were not published. In an analysis of the lively reactions to the publication of Jesień średniowiecza, he distinguishes three types of reactions (Lipoński 2015: 10-15). The first represents the opinion of the dominant communist cultural opinion, according to which Huizinga was a ‘catastrophist’, whose overall conclusions are erroneous and thinking often contradictory. Polish readers can profit from reading Huizinga’s work, but it should be presented with a commentary that highlights the ideological errors in his thinking.[v] In addition to this attitude, however, there were also reactions with a much more positive evaluation, for instance a review by Stanisław Łoś, which allowed for the indirect and figurative expression of the opinions of the Catholic Polish intelligentsia. The fact that such reactions to the book were permitted gave further signals to readers about the thaw in ideological restrictions after the Stalinist period (Łoś 1962: 1-4).[vi] A third type of reaction, represented for instance by the philosopher Leszek Kołakowski, was less radically critical and expressed admiration for the breadth of examples from art and literature that Huizinga presented in Herfsttij, but also added a methodological critique concerning the lack of an empirical categorization of these examples.[vii]

In 2016, the book was retranslated by the polyglot, writer, poet, translator, and editor Robert Stiller. In this edition, in stark contrast to the collaborative production visible in the first translation, Stiller not only translated Huizinga’s text and the excerpts of poetry, but also wrote the introduction and afterword. In the introduction, Stiller criticizes Brzostowski’s translation. He considers this translation to be long-winded, pretentious, and careless.[viii] Stiller claims to have used an unspecified Dutch version of Herfsttij and the second English translation, in case of doubt. Stiller was a polyglot and translated literature from many languages, but Dutch was not one of them. Furthermore, the publication was not printed with the support of the Dutch Foundation of Literature. Since Poland has several good translators from Dutch, the foundation would certainly have required the publisher to contract an experienced Dutch-Polish translator to qualify for the translation subsidy. It remains unclear which was the source language of the second Polish translation, but it can be stated with almost complete certainty that it was not simply based on the Dutch original.[ix]

[i] We wish to thank Małgorzata Dowlaszewicz and Michal Hynas for their assistance with the Polish material.

[ii] As well as a chronology by Helena Kahanowa, and an index of the persons by Janina Wiercińska.

[iii] This edition was reprinted in 1967, 1974, 1992, 1996, 1998, 2002, 2003, 2005.

[iv] A single chapter of Huizinga’s Erasmus had already appeared in 1959, translated from the German. Huizinga 1959.

[v] For example, in the review: Grzybowski, 1962: 1. in Lipoński 2015: 9-42.

[vi] Quoted by Lipoński 2015.

[vii] Kołakowski, L. (1962).

[viii] Stiller’s afterword, in Huizinga 2016: 377.

[ix] Unfortunately, the translator cannot be asked to clarify these questions since he passed away in the years of the publication.

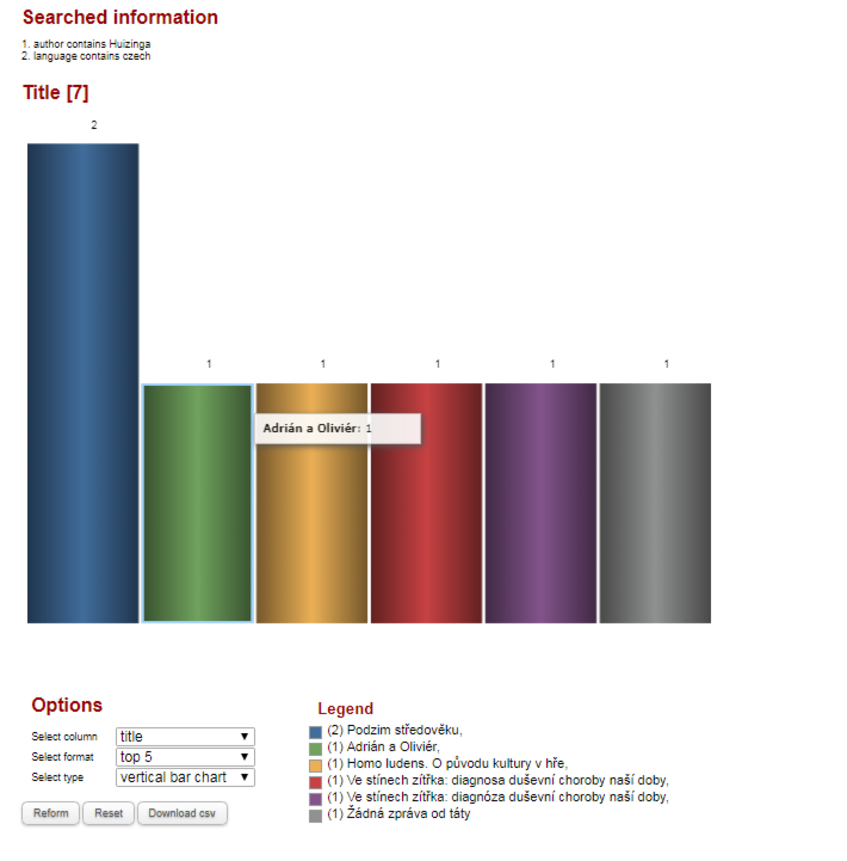

Huizinga in Czech and Slovak

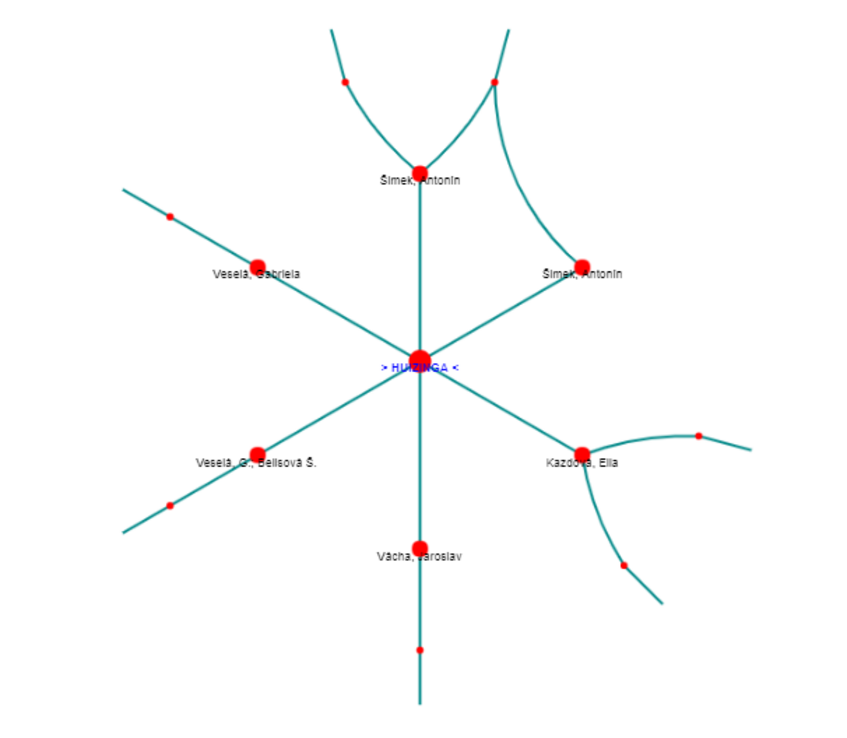

Surprisingly, the complete Herfsttij was not published in Czech and Slovak until the end of the 20th century. The first Czech translation appeared in 1999 at the Jinočany publishing house in a translation by Gabriela Veselá under the title Podzim středověku [literal translation The Autumn of the Middle Ages].[i] The translation was made from the German authorized translation Herbst des Mittelalters by Kurt Köster and Tilly Jolles-Mönckeberg. The translator, Gabriela Veselá was at that time a member of the Czech Literature Institute at the Czech Academy of Sciences and a lecturer at the Department of German Philology at Charles University in Prague (Engelbrecht 2017: 79). The French text fragments were translated by Šárka Belisová. Even though this first Czech edition was published eighty years after the original, it includes neither an explanatory foreword nor an afterword. It does include 12 pages of black and white illustrations. A second edition of this same translation followed in 2010, this time at the literary publisher Pasenka in the series Historická paměť [Historical memory], again without an introduction, but this time with 8 pages of black and white and coloured illustrations.

The editions were positively received, with a frequent emphasis on the literary qualities of the book, for instance in a review by Ladislav Nagy:

It is obvious that the book, since the aspects mentioned above, is very close to literature. And indeed, Huizinga is an excellent stylist, an excellent narrator who proves more than favorable to what will be emphasized by Hayden White, namely the illusiveness of the distance between historiography and fictional literature. Huizinga's early work is so convincingly accurate especially because of its literary qualities and the delicate harmony between content and form (Nagy 2000: 20).[ii]

The 2010 edition was also received with enthusiasm (Vaverka 2010: 136-137). The reviewers generally did not consider it to be dated, and in one case it was even celebrated for its “new approach”.[iii] In Martin C. Putna’s review, it was associated with another book by Huizinga: “This work also forms the basis for a synthesizing work that was released in 1935 under the title In the Shadow of Tomorrow.” (Putna 2000: 14) It is significant that he contextualized the new Czech translation by referring to In the Shadow of Tomorrow, since this was Huizinga’s first book to be translated into Czech in 1938, and it was republished in 1970.[iv]

Relations of Czech translations Huizinga, data from the DLBT.

Statistical overview of Huizinga's translations in Czech, data from the DLBT.

There had been an attempt to make a Czech translation of the Herfsttij before the war. In his article about Huizinga’s reception in Bohemia, Wilken Engelbrecht writes about three partly overlapping groups of Czech intellectuals who were influenced by Huizinga’s oeuvre beginning in the 1920’s. Czech historians, who read his work in German, and discussed and wrote reviews of it from the 1920’s on, protestant scholars who were mainly interested in the philosophical aspects of his writings, and a discernible wave of reception in the 1930s within a group of young historians with a Marxist orientation, The Historical Group (Historická skupina). At the end of 1939, this group drew up a plan to publish a series of historical works, both by local historians and studies translated from other languages, in cooperation with the Družstevní práce publishing house. The list included Herfsttij, which was to be translated from the French translation of 1932, but the project was aborted due to the outbreak of WWII (Engelbrecht 2017: 73).

In an article dedicated to the Slovak reception of Huizinga’s oeuvre, Adam Bžoch argues that from 1946-47 onwards the Dutch scholar’s writings provoked a vigorous debate in the conservative circle of Catholic intellectuals grouped around the periodical Verbum, who were primarily interested in theological, literary and philosophical questions (Bžoch 2017: 87). They were the first to devote attention to Huizinga, when in 1946 they published a review of the French edition of Huizinga’s cultural critical political testament, Geschonden wereld.[v] This was followed by a longer biographical article about Huizinga in the same periodical, and a Slovak translation of about one third of the first chapter of Herfsttij under the title Napätie života (‘Die Spannung des Lebens’) made from the German by Valentín Kalinay in 1947.[vi] The translation of the complete Herfsttij only followed more than forty years later, in 1990, which nevertheless preceded the Czech translation. It was published in an integral double edition together with Homo Ludens. Both works were translated by Viktor Krupa, who used the 1987 English translation of Herfsttij for his Jeseň stredoveku [literal translation The Autumn of the Middle Ages], and the 1944 authorized German translation of Homo Ludens as a source text. The edition is accompanied by a lengthy afterword and detailed notes by Vojtech Kopčan (Bžoch 2017: 95).

Source:

Brems, Elke and Réthelyi, Orsolya. 'Rescuing something fine. Huizinga's Herfsttij der Middeleeuwen as World Literature.' In: Theo D'haen (red). Dutch and Flemish Literature as World Literature. London/New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2019

[i] I wish to thank Klara Šrejmová for her assistance with the Czech material.

[ii] See also the review by Martin C. Putna.

[iii] Cf. Vít Vlnas, 2000.

[iv] For the publication history of the Czech translations of Huizinga’s works see Engelbrecht 2017: 71-85.

[v] No reaction can be found in the Slovak periodicals either to the German translations of Huizinga’s work or to the 1938 Czech translation of In de schaduwen van morgen. Bžoch 2017: 86-87.

[vi] Huizinga, Johan. 1947. „Napätie života.“ Verbum II, 1: 23–28. [´s Levens felheid/Spannung des Lebens]. For the publication history of the Slovak translations of Huizinga’s works see Bžoch 2017: 98.