Herfsttij der Middeleeuwen: the English Translation

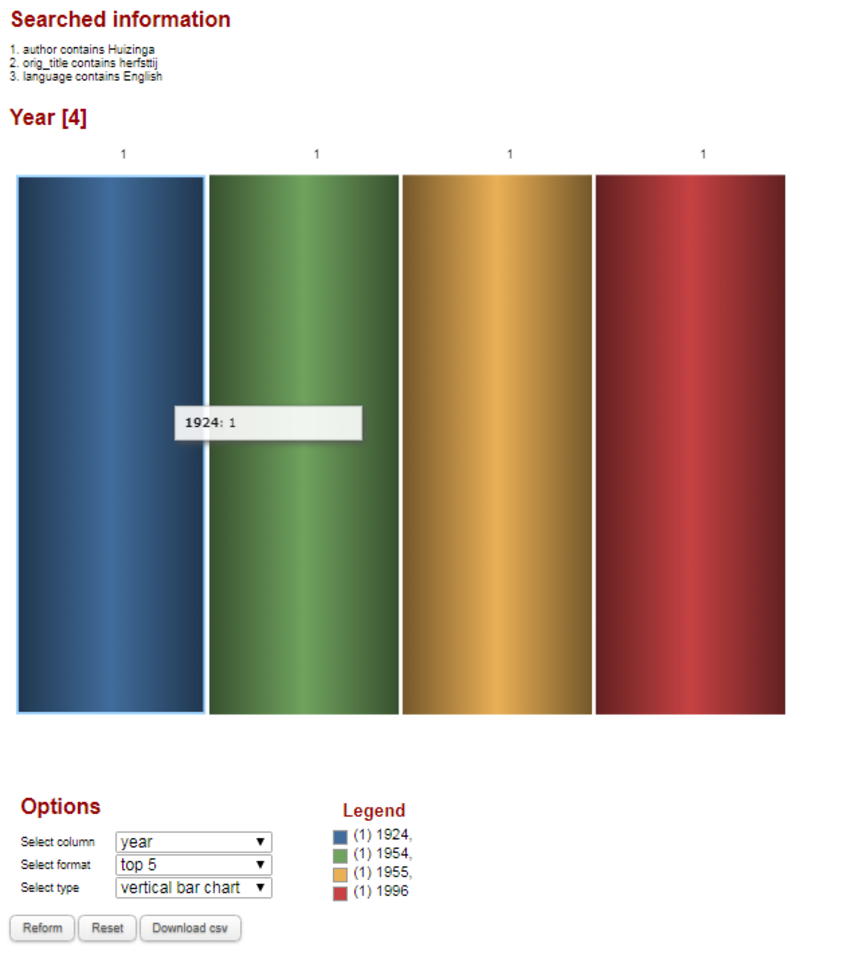

Publication history of Herfsttij der Middeleeuwen in English. Data from the DLBT.

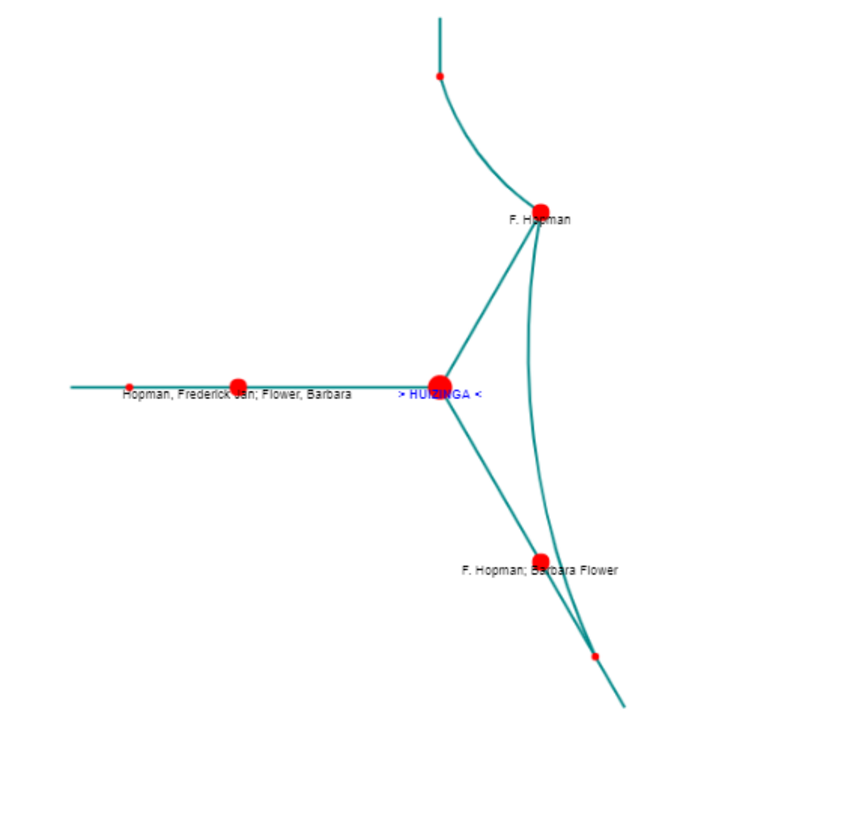

Fritz Hopman as Huizinga's translator. Data from the DLBT.

Herfsttij der Middeleeuwen: the English Translation

Huizinga himself was very concerned and involved in the international dissemination of his book. The idea of an English translation had already been voiced in 1920, at the University of Columbia in New York. A student of Adriaan J. Barnouw, who held the Queen Wilhelmina lectureship there at the time, was apparently interested in working on the translation, to Huizinga’s great delight. On 13 July 1920, he wrote the following to Barnouw: “As far as I am concerned, I would enjoy it very much if the book were to be published in English translation, and I am of course prepared to contribute to achieving this aim. The translation will not be easy, and I must hope that your student will muster the courage to undertake it.” (Huizinga 1989-1991: letter 302) In that period, Huizinga was in the process of revising the book for its second edition, “to clarify terse passages.”[i] (Huizinga 1989-1991: letter 319) The American translation was never found.

In the meantime, however, through the mediation of Sir J. Rennell Rodd, a British publisher had expressed interest in an English translation. The problem was that the publisher, Edward Arnold, could not find anybody to evaluate the source text. He wrote to Huizinga on March 1st 1923: “Unfortunately we do not know of any competent reader who is thoroughly conversant with the Dutch language, but I understand that your book is being translated into French, and if it was possible to see the French translation we could probably form an opinion more easily than from the original Dutch.” (Krul et al 1989: letter 465) Huizinga duly dispatched the French translation, but added the following: “the book has been considerably abridged in the French translation and all the references left out. The Dutch edition is nearly one third larger than the French (…). If there should be an English edition, I think it ought to be translated after the complete Dutch text, with all the references. Perhaps some details might be shortened.” (Krul et al: letter 466) Huizinga backed down shortly afterwards, writing: “I can agree in principle with the idea of an English edition of my book in the abridged form.” (Krul et al: letter 472)[ii]

In the foreword we read that it was “not a simple translation of the original Dutch (…) but the result of a work of adaptation, reduction, and consolidation under the author’s directions.” (Huizinga 1924: v-vi) This all occurred under the auspices of Huizinga himself.[iii] This translation history likewise entails an evaluation of the book: the original text was deemed less appropriate for the English market than the first (unpublished) French translation. Huizinga was very flexible with regard to his text, given that there is not just one authorized version either of the source text or of the translated version.

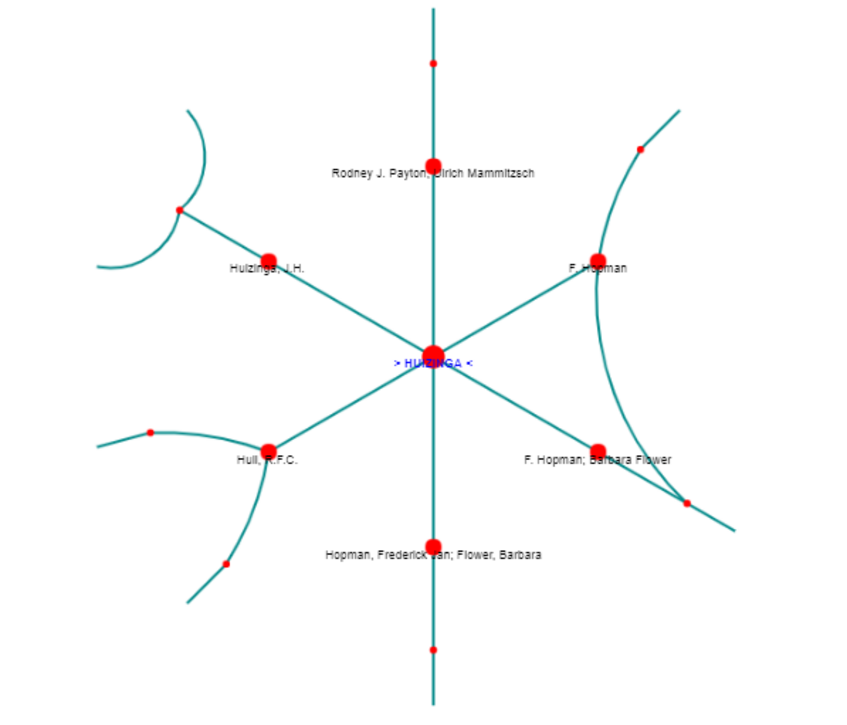

Just like in Germany, the translation in English, made by Fritz Hopman, was well-received both in the UK and in the US. In 1925, G.C. Sellery e.g. wrote in The American Historical Review: “The breadth of its scholarship, the riches of its matter, afford ample pabulum for historical enlightenment and rumination upon the variety and persistence of human traits.”

[i] “Wat mij betreft, ik zou het hoogst aangenaam vinden, indien van het boek een Engeslche vertaling verscheen, en natuurlijk zeer bereid zijn, tot het welslagen daarvan mee te werken. Gemakkelijk zal het vertalen niet zijn, en ik moet hopen, dat Uw leerlinge er den moed toe vindt. Indien daartoe kan bijdragen, dat ik genegen ben, geregeld over de vertaling te adviseeren, wil ik gaarne, dat U haar daarvan de verzekering geeft” and “om gedrongen passages te verduidelijken”

[ii] And ultimately the publisher decided: “We should be pleased to undertake the publication of an English translation of your book on ‘The Decline of the Middle Ages’, provided that the English version does not exceed about 110,000 words, which corresponds roughly to the French version you kindly showed us. We think that the majority of the footnotes should be omitted” (Krul et al 1989: letter 477)

[iii] Huizinga wrote to Barnouw concerning the London translation: “It will be an abridged edition (…) The translation was done by Hopman, but I also had a considerable share in it because I was able to collaborate with him very pleasantly and even suggest whole passages when his translated was not satisfactory.” (Krul et al 1989: letter 526). “Het wordt een verkorte redactie (…) De vertaling is door Hopman gemaakt, maar ik heb er zelf ook vrij wat aandeel aan, doordat ik met hem op een heel prettige wijze kon samenwerken en heele passages zelf suggereeren, als mij zijn vertaling niet bevredigde.”

Autumn of the Middle Ages - A Century Later

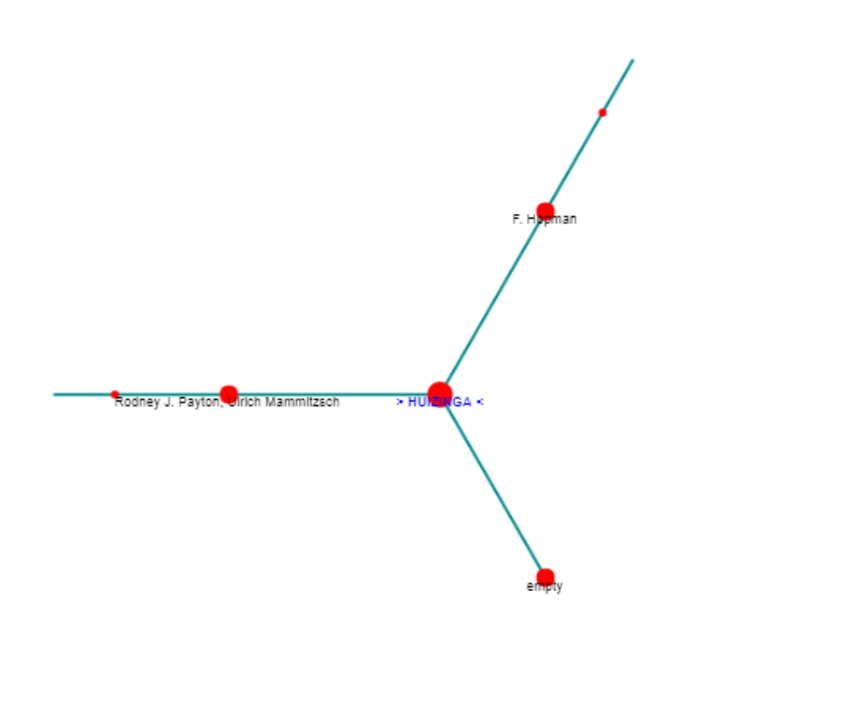

Seventy years later, in 1996, Rodney J. Payton and Ulrich Mammitzsch ventured to retranslate the book. They used Herfsttij in their lectures and found the available text inadequate when compared to the original, which they thought was a far better book than the Hopman translation. In their introduction they described “a certain feeling of being the rescuers of something fine that had been corrupted and undervalued.” (Payton 1996: IX) They appreciated the first translation for bringing the book to the attention of the English-speaking world, but did not think that it did justice to the original. They were shocked that as a consequence, a book was circulating in the English-speaking world that was unrecognizable to Huizinga experts and readers: “Is it possible that English-speaking historians have been discussing this book with their foreign colleagues without realizing that they were reading a significantly different text? If this is so, it is a primary justification for the present translation.” (XIII) Mammitzsch – who had passed away by the time of publication – and Payton based their translation on the second Dutch edition of 1921: “the second represents his thinking at its most seminal stage” (XVII), an evaluation that is of course entirely their own.

Herfsttij der Middeleeuwen and its English translators. Data from the DLBT.

All translations of Huizinga in English. Data from the DLBT.

The new translation by Payton and Mammitzsch did ensure renewed interest in the book, and long reviews were published in academic journals, often accompanied by extensive critical assessments of its value and significance.[i] Everyone agreed that it had been profoundly influential. Peters and Simons remarked that it has been particularly influential in the context of American academic curricula: “In fact, at least in the United States, its wide use in large survey courses has made it a familiar component of the view of the later Middle Ages held by many people.” (1999: 589)[ii] In 2016, Moran brought the question of influence into sharp relief: “Long after most monographs have been buried on library shelves, Huizinga continues to be read and nearly a century later, he still speaks to people.” (413) This becomes even clearer when we consider that a new translation is currently being completed by Diane Webb. It is slated for publication in 2019 and is being entirely subsidized by the Dutch Foundation for Literature. They hope to further exploit this translation as an intermediate text for new translations into languages for which no translators who are proficient in Dutch can be found.

Source:

Brems, Elke and Réthelyi, Orsolya. 'Rescuing something fine. Huizinga's Herfsttij der Middeleeuwen as World Literature.' In: Theo D'haen (red). Dutch and Flemish Literature as World Literature. London/New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2019

[i] See e.g. Bellitto 1997, Staples 1999, Midgley 2012. Krul 1997 offers a well-informed essay on the production history, context, reception, critique, etc. The translation also received extensive attention in the popular press: The Guardian, London Review of Books, Times Literary Supplement, Observer, The Los Angeles Times Sunday Book Review, The New Yorker, Publishers Weekly, The Wall Street Journal.

[ii] They also provide a survey of the reception of the book in the second half of the 20th century.