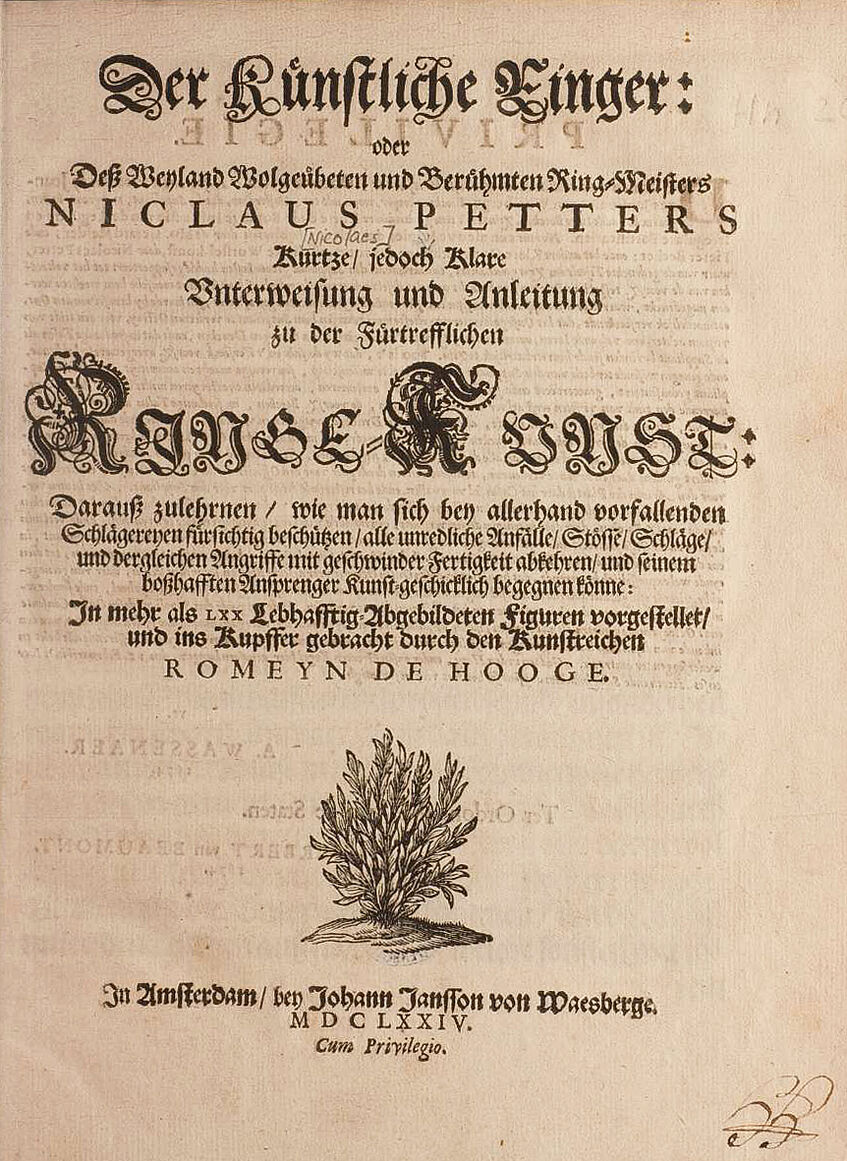

Nicolaes Petter, "Der Künstliche Ringer". Illustr.: Ins Kupffer gebracht durch den Kunstreichen Romeyn de Hooge. – Amsterdam : Johannes Janssonius van Waesberge, 1674

“Only a small number of martial treatises that were produced in the Low Countries are known to exist at present. Of these treatises, only five were written in the Dutch language (or a predecessor) before the 19th century, and the earliest three of these are of the fragmentary nature or very short…

Worstel-Konst (Der Künstliche Ringer) is often recognised as 'the finest of all wrestling books – and deservedly the most famous'. In his treatise, Petters presents a number of scenarios and ways to deal with them. These scenarios include being pushed in the chest, being grabbled by the hair, being punched, and having a knife drawn on you. The title page of this treatise claims that the techniques shown were devised by the author himself, which may certainly be true in the case of some of the techniques shown.

While some of Petter's techniques seem rather outlandish, the treatise was obviously quite popular, and not just in the Nederlands, where it was re-printed twice in Amsterdam. In 1712, a French translation was published in Leiden, and German translations were for instance published by Theodori Verolini (uncredited) in his treatise printed in Würzburg in 1679, and Karl Wassmannsdorff in 1887 in Heidelberg, while Johann Andreas Schmidt included parts of Petter's work in the wrestling part of his 1713 treatise.”

from "Late Medieval and Early Modern Fight Books. Transmission and Tradition of Martial Arts in Europe (14th-17th Centuries)"

„Nicolaes Petter was a German born in Hessen who had come to Amsterdam as a wine trader, and who later opened a wrestling school. He died in 1672 at the age of 48 and his masterpupil, Robbert Cors, took care of the manuscript's publication. The main part of it consisted of some 70 illustrations by the famous engraver Romeyn de Hooghe, a protégé of stadtholder William III. Romeyn de Hooghe may have practiced in Petter's school. The wrestlers are clearly represented as middle to upper class. They wear Louis XIV-style wigs and fine closing. Although they opponents, too, are decently dressed, the title page recommends the art taught in the book as 'very useful and advantageous against all quarrelsome persons prone to beating or those who threaten someone with a knife or try to injure him'. The preface speaks of 'fight-craving malefactors.' The knife fighters, cleverly disarmed by the unarmed wrestlers, wear shabby clothes and typically lower-class hats. They are termed 'the most unreasonable and unrestrained scoundrels, whose hotboiled brains cannot be tempered by reason.' Wrestling is obviously recommended as an alternative to self-defense against a knife with a stick. To foreigners, the art taught in the book served as an alternative to defense with a rapier. With William III, who was to become king of England, indirectly involved, the book had a truly international dimension. “

from Petrus Cornelis Spierenburg, "A History of Murder, Personal Violence in Europe from the Middle Ages to the Present"

“Romeyn de Hooghe was the most inventive, prolific, and versatile graphic artist of the Dutch Republic in the late seventeenth century. He led an extraordinary life: one that proceeded from very austere circumstances – though not quite rags – to riches, and was marred by a never-ending stream of scandalmongering.

The credit side of his biography shows a vast oeuvre of graphic works, unsurpassed in magnitude and originality. Having enjoyed a sound classical education, he was wellread in ancient and modern literature and history. In middleage, he obtained a law degree and served as a magistrate in Haarlem, where he established a drawing academy. During the six-year war with France (1672–1678), he glorified Stadtholder William III of Orange in a massive array of patriotic prints. Later, he became the stadtholder-king’s premier propaganda artist, extolling to a reluctant Dutch audience the virtues of William’s invasion of Britain, the Glorious Revolution, and the ensuing Nine Years’ War (1688–1697). He lambasted William’s adversaries, especially Louis xiv and James ii, with acerbic satirical prints of striking originality. During the latter part of his life, he broadened his activities to become an all-round designer of statues, wall and ceiling paintings, triumphal arches, ornamental cups and gob-lets, and stained-glass windows. He distinguished himself as the author of learned works about the institutions of the United Netherlands, religious iconography, and the genealogy of world religions. He launched the world’s first illustrated satirical journal. He allegedly invented new methods to make stained glass and print cotton, and engineered a sailing bomb to be employed in naval attacks. He set up a sand-stone business and ran a spy network. Having begun his career as a simple artisan, he became a universal artist, an uomo universale in the grand Renaissance and Baroque tradition.

In spite of de Hooghe’s astonishing and wide-ranging talents, his life was not an unqualified success. There was an unbalanced and roguish streak to his character that drove him to take vast and unwarranted risks, threatening to destroy his career time and again. He and his family were haunted by controversies, calumny, and slander. In a scurrilous novelette and a flood of libels, he was accused of making pornographic prints, lasciviousness, godlessness, blasphemy, fraud, embezzlement, and thievery. These charges, and the recklessness with which he attempted to refute them, make his biography read like a picaresque novel.

Shortly after his death, whilst duly recognizing his gifts as a designer and etcher, art critics painted a pitch-black picture of his character, privileging moral righteousness over a dispassionate exploration of the facts. Only recently did historians pronounce a more positive verdict. Otto Benesch, for example, regarded Romeyn de Hooghe as ‘the most brilliant Dutch illustrator and one of the most important etchers ever’.”

from Henk van Nierop, “The Life of Romeyn de Hooghe 1645-1708. Prints, Pamphlets, and Politics in the Dutch Golden Age”