Olfert Dapper

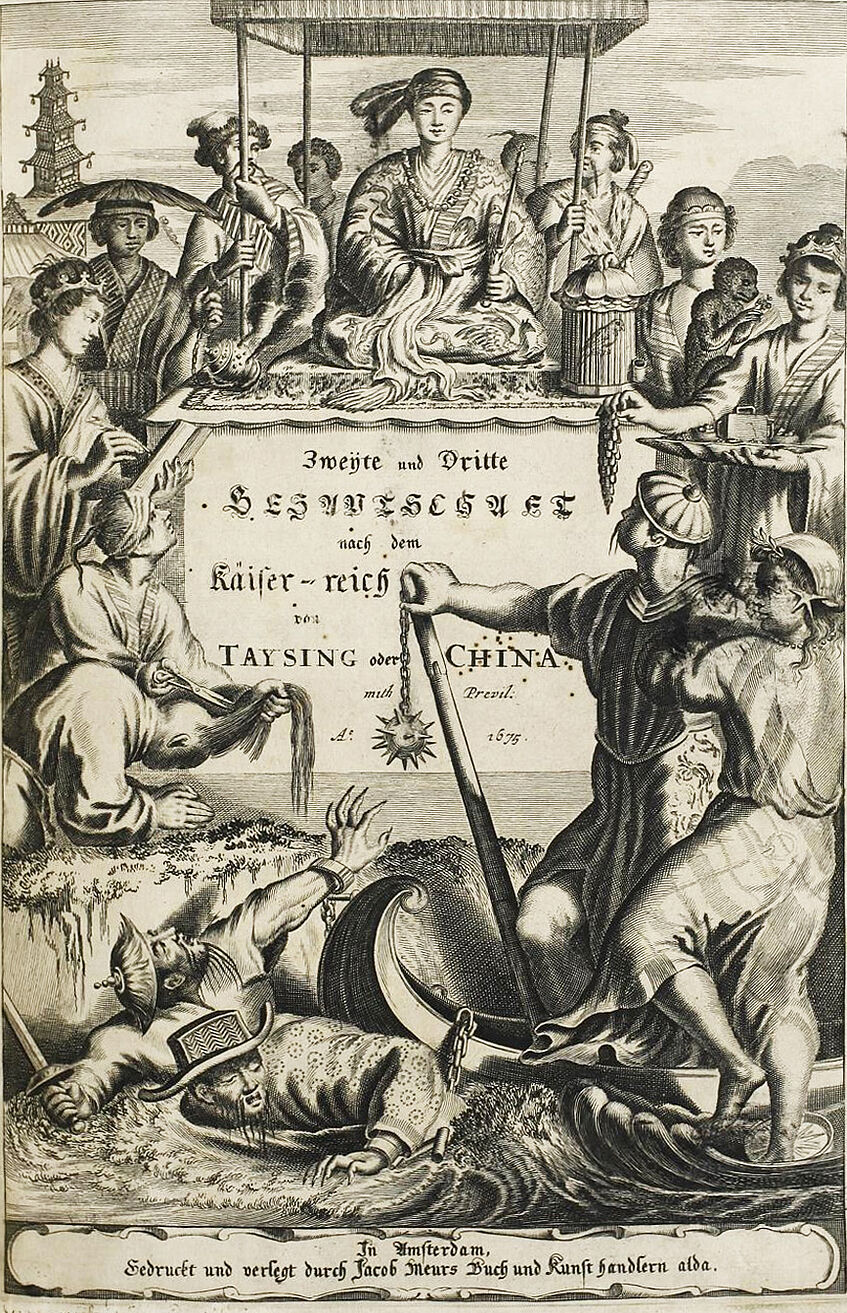

Olfert Dapper, "Gedenkwürdige Verrichtung Der Niederländischen Ost- Indischen Gesellschaft in dem Käiserreich Taising oder Sina, durch ihre Zweyte Gesandtschaft An den Unterkönig Singlamong und Feldherrn Taising Lipoui". Amsterdam : Jacob van Meurs, 1674

Cloves, nutmeg, myrrh and pepper – in the 17th century, these words were synonymous with the words power and influence. Europeans dreamed of India and access to the desired spices. Expensive expeditions outfitted repeatedly, were again and again exposed to the dangers of the sea route, countries competed and fought over incense and cinnamon – with each other and with the natives.

Spain and Portugal were the most powerful maritime powers and could protect their monopoly on the sale of expensive spices. In 1595, the first official merchant fleet left Holland, rushing to Asia. 100,000 guilders were supposed to buy spices in Ostindia. This first official expedition became so successful that numerous other trading expeditions followed. Various trading companies equipped their own ships and sent them to Asia for precious spices. For each of the expeditions, Dutch merchants united and founded trading companies that competed with each other and quickly disintegrated.

The idea of a trading community that would bring together all competing trading companies sending expeditions to Asia and that would benefit all evolved next. Already in 1602, the Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie (VOC) was founded with the support of Prince Maurice of Orange, stadtholder of the Netherlands. It soon became the largest monopoly in the trade on overseas spices, which it remained for about 200 years.

The Dutch States General secured the right for the VOC to monopolise any goods traded between the Netherlands and all countries lying east of the Cape of Good Hope and west of the Strait of Magellan for 21 years. The VOC was set up as a joint-stock company. It was very popular and had an excellent reputation so that the citizens of the Netherlands bought shares and became shareholders in the largest and most powerful trading community in the world.

The VOC had the right not only to enter into trade deals, but also to establish its own fleet and assemble its army, build military fortifications and conclude state-level agreements. In Ostindia, the company acted as a real sovereign state, although it officially represented the Netherlands. Formally, the Dutch forces were supposed to defend the Dutch fortifications and plantations, but in reality, they conducted invasive military campaigns until they finally pushed Portugal out of the region.

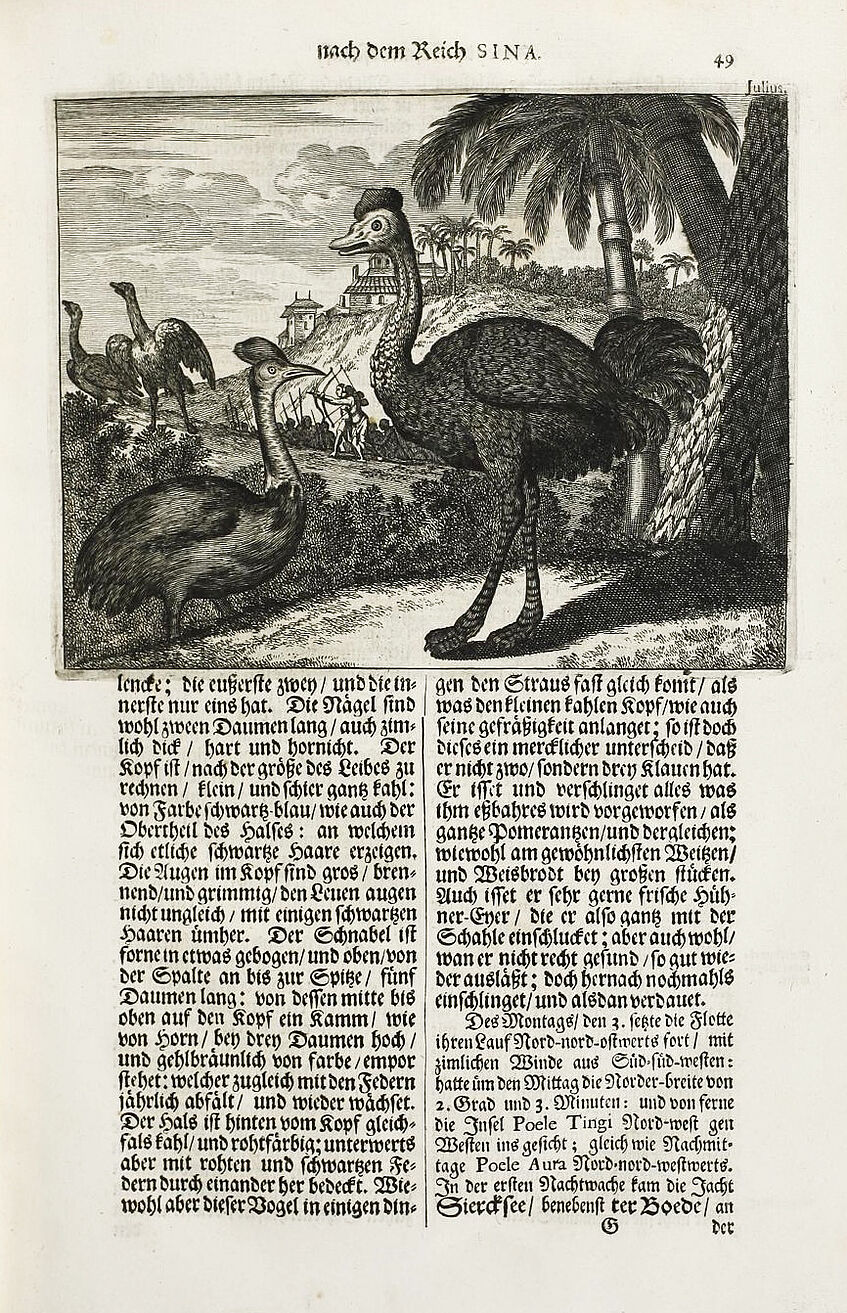

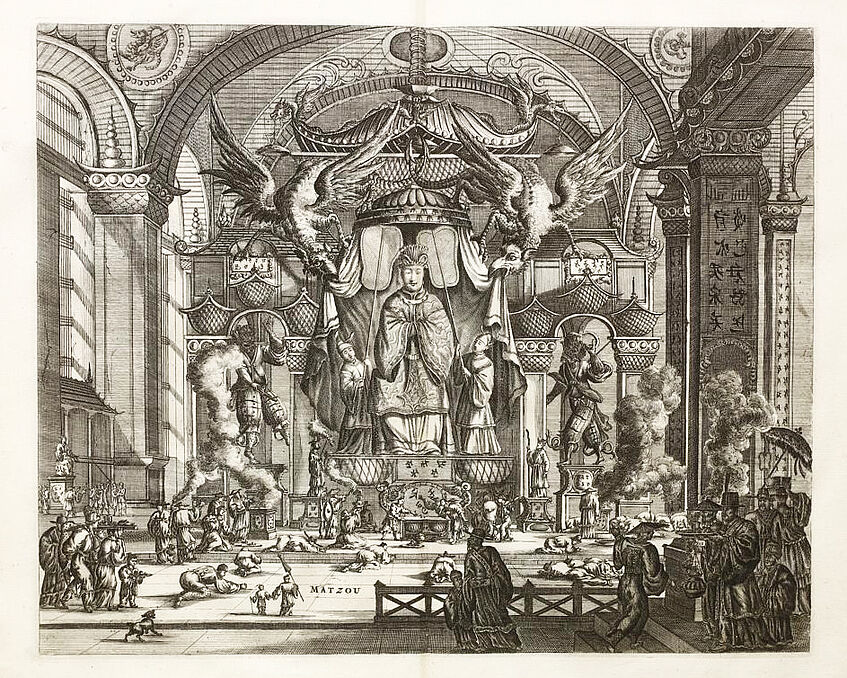

In the mid-17th century, the VOC made attempts to reach the court of the Emperor of China in order to gain the opportunity to trade with this country. The first embassy in 1655-1657 failed and in 1666, a new expedition was prepared. Peter van Hoorn and Constantijn Nobel led the expedition. 23 people, including two trumpeters, a cook, a surgeon with two assistants, a draftsman and son of van Hoorn Joan, went from Batavia to the shores of China. It took the expedition almost half a year to travel from the coast to Beijing – by land and on river vessels. Everything that was seen and heard was sketched and recorded: Peter van Hoorn’s expedition documented everything from the customs and everyday life of the Chinese, to the costumes and hats of ordinary citizens and Chinese rulers, and the whole life of the Chinese people from birth to death.

“The mission of Pieter van Hoorn, an Amsterdam patrician, to China in the middle of the seventeenth century is another example of misjudgement between people of different cultures. His embassy was well prepared: the Council of the Indies had consulted various archives on relations with China and had set out extensive instructions on its goals. Van Hoorn had carefully selected his retinue. One can safely say that both the envoy and his supervisors had done everything that was expected of a European embassy. However, the long and costly enterprise did not bring the desired result as no direct contact with the emperor was ever established. As his visit drew to an end, Van Hoorn received a letter on the part of the emperor informing the Dutch very politely that they were not welcome and that a visit once every eight years would suffice. Van Hoorn had achieved exactly the opposite of the VOC`s intentions. The Dutch had initiated this expedition in order to gain access to the Chinese market and set up a factory. They had expected to pay visits on a regular basis. But after the audience, the message read ‘Given that your country is very far-off and that very strong winds blow here that cause grave danger to your ships to come over, taking into account that it is really cold here because of hail and snow, it would grieve me deeply if your people came here. So if you really wish them to visit, let them come once every eight years, and not more than a hundred men. Twenty of them can put up camp at the palace. There you can take your merchandise, without having to trade at sea off Canton. This I have decided for your own good, trusting that you will be pleased as well’. The Dutch could put that in their pipe and smoke it. Once every eight years the Dutch were allowed to greet the Emperor on the big audience square among the envoys of many other rulers. In return, they were allowed to conduct a little trade. If ever a diplomatic meeting could demonstrate how strongly the Chinese and European views of embassies differed, this failure would be the one,” wrote Jurrien van Goor, in Prelude to Colonialism. The Dutch in Asia (Uitgeverij verloren, 2004).

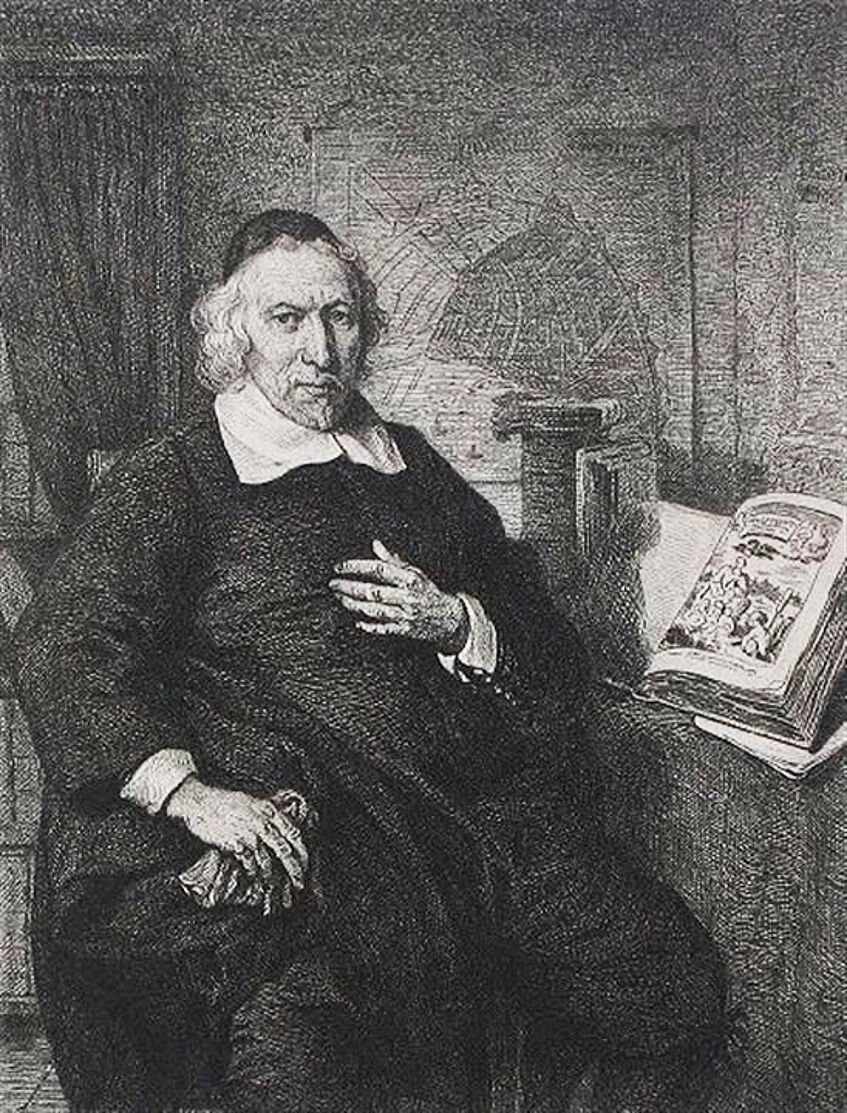

In 1670, the book Gedenkwürdige Verrichtung Der Niederländischen Ost- Indischen Gesellschaft in dem Käiserreich Taising oder Sina, durch ihre Zweyte Gesandtschaft An den Unterkönig Singlamong und Feldherrn Taising Lipoui about the unsuccessful expedition of Paul Hoorn to China, edited by Olfert Dapper, was published. The author of this book never left his native country – he never saw the African countries or China with his own eyes. Yet, his books about travelling these regions became bestsellers.

Dapper was born in 1636 in Amsterdam. Almost nothing is known about his life: He entered the medical faculty of the University of Utrecht but did not complete his studies, devoting all his time to reading and writing. In 1663, he published a historical description of Amsterdam – the book became a bestseller and Dapper decided to focus on the description of different countries overseas. This marked the beginning of his series of geographical books. In 1668, his legendary description of Africa was published, including ethnographic, botanical, zoological and topographical information about the region, which is still an important source of local history for Africanists. After 1670, he published a number of books about the Dutch expeditions to the Far East, the Middle East and Asia.

Dapper used the notes and illustrations provided by the expedition members to write Gedenkwürdige Verrichtung Der Niederländischen Ost- Indischen Gesellschaft in dem Käiserreich Taising oder Sina, durch ihre Zweyte Gesandtschaft An den Unterkönig Singlamong und Feldherrn Taising Lipoui.

Dapper's book was translated into English and German. It was published in London in 1671 and in 1674, a German-language version appeared in Amsterdam.