Gérard de Lairesse, pictured by Rembrandt van Rijn, Oil on canvas, 1665 – in the collection of Metropolitan Museum of Arts

„Anleitung zur Zeichen-Kunst, wie man dieselbe durch Hülffe der Geometrie gründlich und vollkommen erlernen könne“, 1705

Gérard de Lairesse, „Anleitung zur Zeichen-Kunst, Wie man dieselbe durch Hülffe der Geometrie gründlich und vollkommen erlernen könne“. Berlin : Schlechtiger, 1705

“Throughout history many an eminent career has ended in syphilis, but the brilliant career of Gerard de Lairesse (1641-1711) began in syphilis.

de Lairesse was a draughtsman, theatrical set designer, lecturer, writer, theoretician, and perhaps the most celebrated Dutch painter in the years following the death of Rembrandt. It is generally accepted that he suffered from congenital syphilis. That diagnosis has been based almost entirely upon a portrait by Rembrandt in the Lehman Collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Yet, as he painted the portrait, Rembrandt did not realize that he was labelling his younger colleague with syphilis, because at that time the characteristic facial deformities of late congenital syphilis were not recognized and would remain unknown for another 200 years.

The portrait was painted in 1665, when de Lairesse was 24 and Rembrandt was 59. The painting is typical of Rembrandt's late portraits with its broad brush strokes, heavy paint, and soft, dark colours. Rembrandt has pictured the unattractive young man in a sympathetic, dignified, but honest way.

It was not until 1913 that Dr J. H. Hanken first recognized the face in Rembrandt's portrait as that of a victim of congenital syphilis.

What de Lairesse lacked in physical good looks was well compensated by his attractive personality, talent, and intellect, for he was the darling of women, colleagues, wealthy patrons, and students. He first studied art in Liège, where he had been born into an artistic family. A stormy love affair forced him to leave his hometown in 1664. He eventually settled in Amsterdam with his wife and family. (His two sons, Abraham and Jan, would themselves become painters of note.) His success was almost immediate, and he was soon painting monumental historical, allegorical, and mythological works for the walls and ceilings of palaces. Known as ‘the Dutch Poussin’ for his classical French style and taste, he travelled in intellectual circles and appealed to the élite, the connoisseurs, and the aristocrats. In a sharp departure from the Dutch painters of the Golden Age, he found Apollo and Aurora more worthy subjects than the ordinary milkmaids and lace makers of Vermeer. His broad range of talent included music, poetry, and the theatre, and he designed highly successful stage sets for the Theatre of Amsterdam.

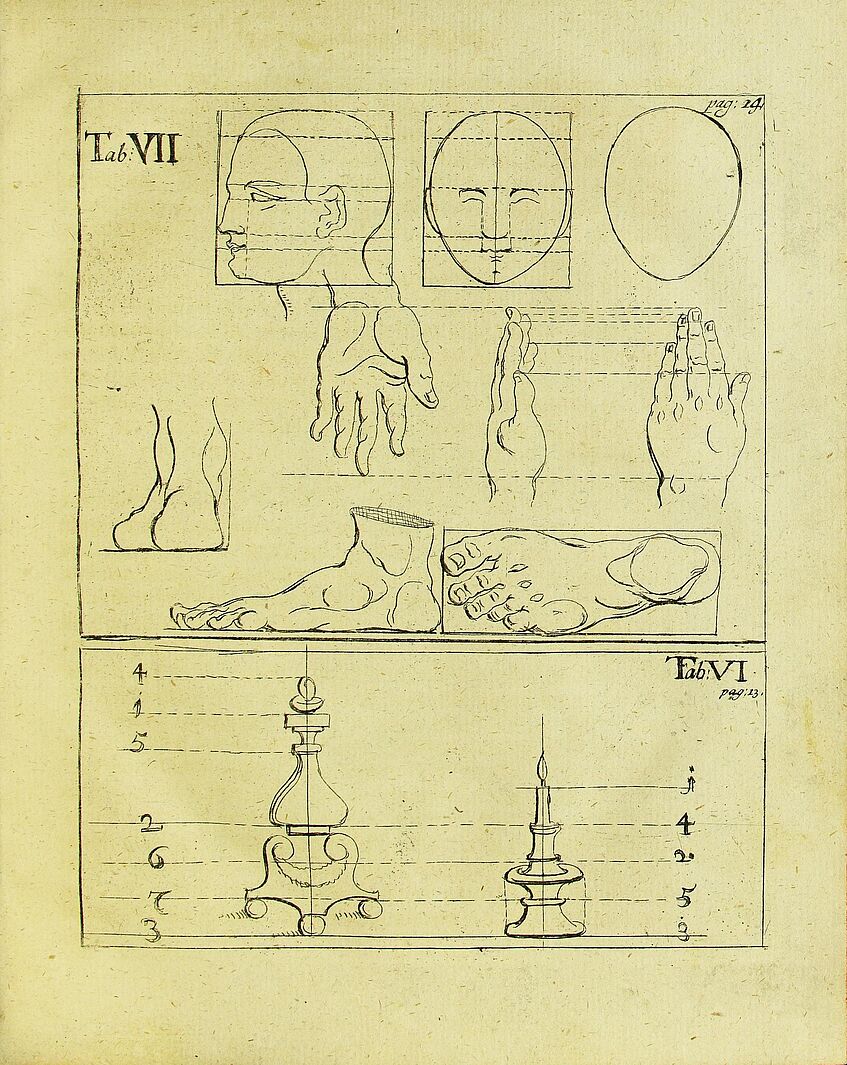

Blindness forced him to quit his career as an artist, whereupon he immediately found success as a lecturer and writer on the theory of art. In 1701 he published his Grondlegginge ter Teckenkonst (Foundations of Drawing). His Het Groot Schilderboek (The Great Book of Painting) in 1707 went through several printings and is one of the most important pieces of early Dutch literature on art. de Lairesse was quick to find fault with the traditional Dutch art of the 17th century, its often vulgar subject matter, its lack of decorum in dressing classical figures in contemporary clothes, its lack of fine linearity. He was a disciplined intellectual, inspired by the notion that only correct theory could produce good art. For him theory meant the strict adherence to rules. The ultimate purpose of the visual arts was the improvement of mankind, and therefore art must, above all, be lofty and edifying. He set forth hierarchies of social status, of subject matter, of beauty itself. The artist, he said, must learn grace by mingling with the social and intellectual élite, must allow his subject matter to teach the highest moral principles, and must strive for ideal beauty.”

from “Gerard de Lairesse: genius among the treponemes”

by Horton A Johnson, in Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, June 2004